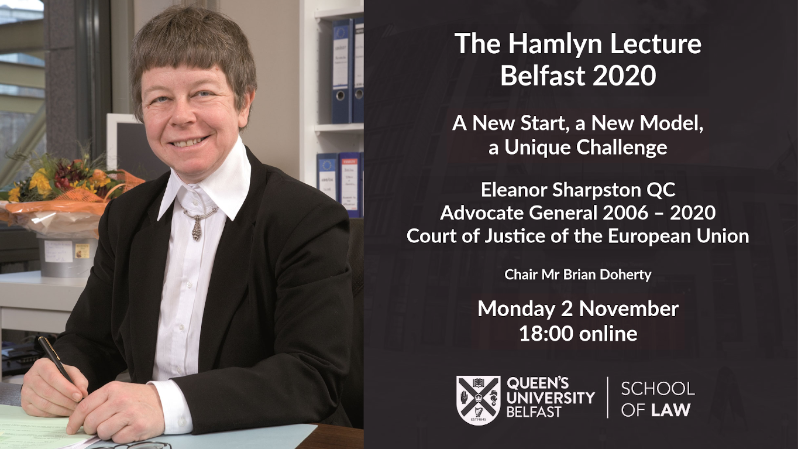

Eleanor Sharpston QC, Advocate General of the European Court of Justice, will be delivering this lecture entitled: 'A New Start, a New Model, a Unique Challenge' to be hosted by the The School of Law, Queen’s University Belfast

- Date(s)

- November 2, 2020

- Location

- online

- Time

- 18:00 - 19:30

- Price

- Free of charge

The founding fathers of the new Europe were idealistic pragmatists. They began by putting coal and steel – the sinews of war – under joint control (thus making future conflict much more difficult) and concentrating on an economic common market with a common external tariff and support for agriculture. Very early on, seminal legal choices were made about the nature, role and authority of the new shared legal system – a system that had somehow to ‘dock’ with the individual disparate national legal systems of the constituent Member States. The doctrines of primacy, supremacy and direct effect, the principle of effectiveness (‘effet utile’) and the parameters of the system of remedies – all ‘created’ by the ECJ, but built on drafting endorsed by the Member States as the masters of the Treaties (‘die Herren der Verträge’) – have played an enormous part in shaping a union of states that is, necessarily and intentionally, radically different from a loose economic confederation linked by a standard international law treaty. The creation of the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice (the ‘AFSJ’), whilst essential, has introduced EU norms into parts of law – immigration law and asylum, police and judicial cooperation, criminal law, even family law – that are much more sensitive and closer to cherished concepts of the State’s imperium than laying down uniform standards for widgets.

As the project evolved from the European Economic Community to the European Community and then the European Union, it grew in membership, in diversity and in scope. That in turn posed an immense technical and intellectual challenge for the project’s legal system: EU law. To what extent can it (should it?) adjust, now that there are not six but 27 different national traditions and legal systems to be borne in mind? How should EU law interact with national law (particularly national constitutional law and its national guardians, the national constitutional courts), with the ECHR and the ‘Strasbourg court’ and with international norms? How (and why) is a European Union under the rule of law different from a union based on shared economic or political aspirations that can be horse-traded away if times and popular thinking change?

| Name | Deaglan Coyle |

| Phone | 02890973293 |

| d.p.coyle@qub.ac.uk |