Vahni Capildeo

Trinidadian Scottish writer Vahni Capildeo’s books and pamphlets extend from prose poetry into immersive theatre. Vahni is a Contributing Editor at the Caribbean Review of Books and has held numerous prestigious academic Fellowships.

Their work has been honoured by the Cholmondeley Award and the Forward Poetry Prize for Best Collection. Recent works include Venus as a Bear (Carcanet, 2018), Skin Can Hold (Carcanet, 2019), and Odyssey Calling (Sad Press, 2020). The forthcoming collection Light Sites will be published with Periplum.

Vahni joined us for a few visits in 2019-20, where students (and staff) benefitted from 1:1 feedback sessions and rigorous discussion groups. Together with Fulbright Scholar for 2019-20 Jenny Browne, Vahni was instrumental in leading discussion and developing new writing in this year's Ekphrasis Project which focussed on a single exhibition, Changing Views: the Artist as Traveller, at the Ulster Museum.

During a locked-down second semester, they contributed to the virtual film events Changing Views and SHC Presents... HELP, both available to view on QFT Player, and to our Writers' Rooms series, which you can read below.

Ekphrasis with Vahni Capildeo

Our regular Ekphrasis project received a boost with the arrival of SHC Fellow Vahni Capildeo and Fulbright Scholar Jenny Browne. Together, we produced a pamphlet of new poems, launched as a virtual exhibition tour with readings - the short film Changing Views can be viewed here.

Read more, and download the Changing Views pamphlet here...

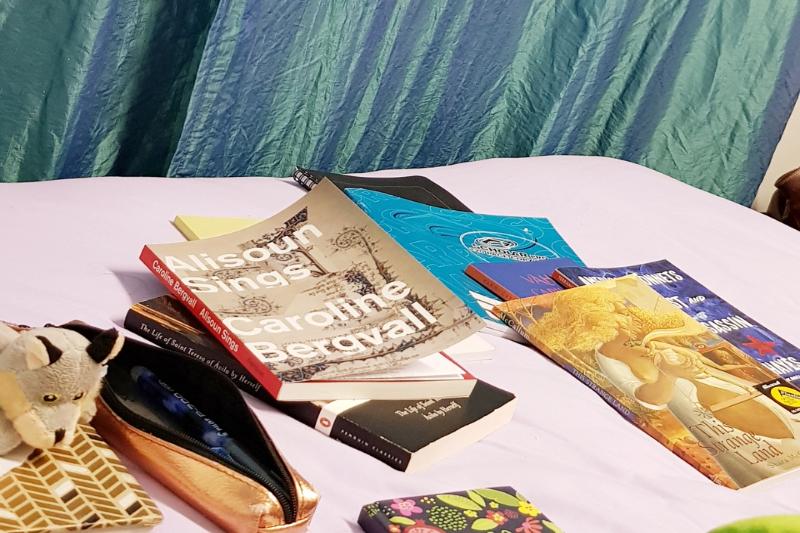

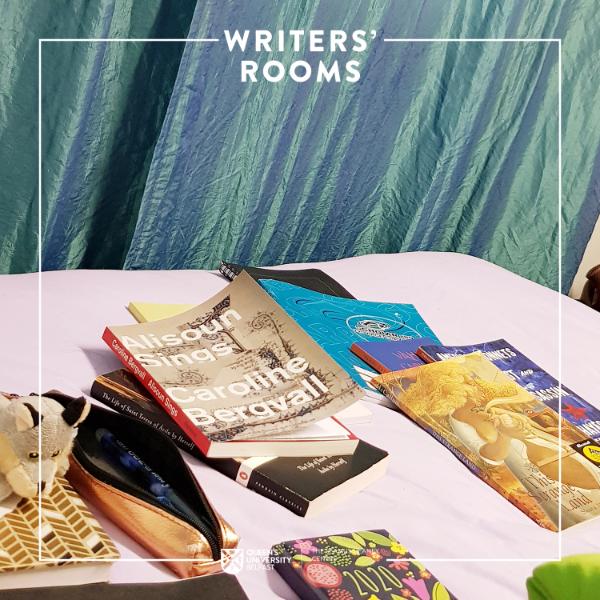

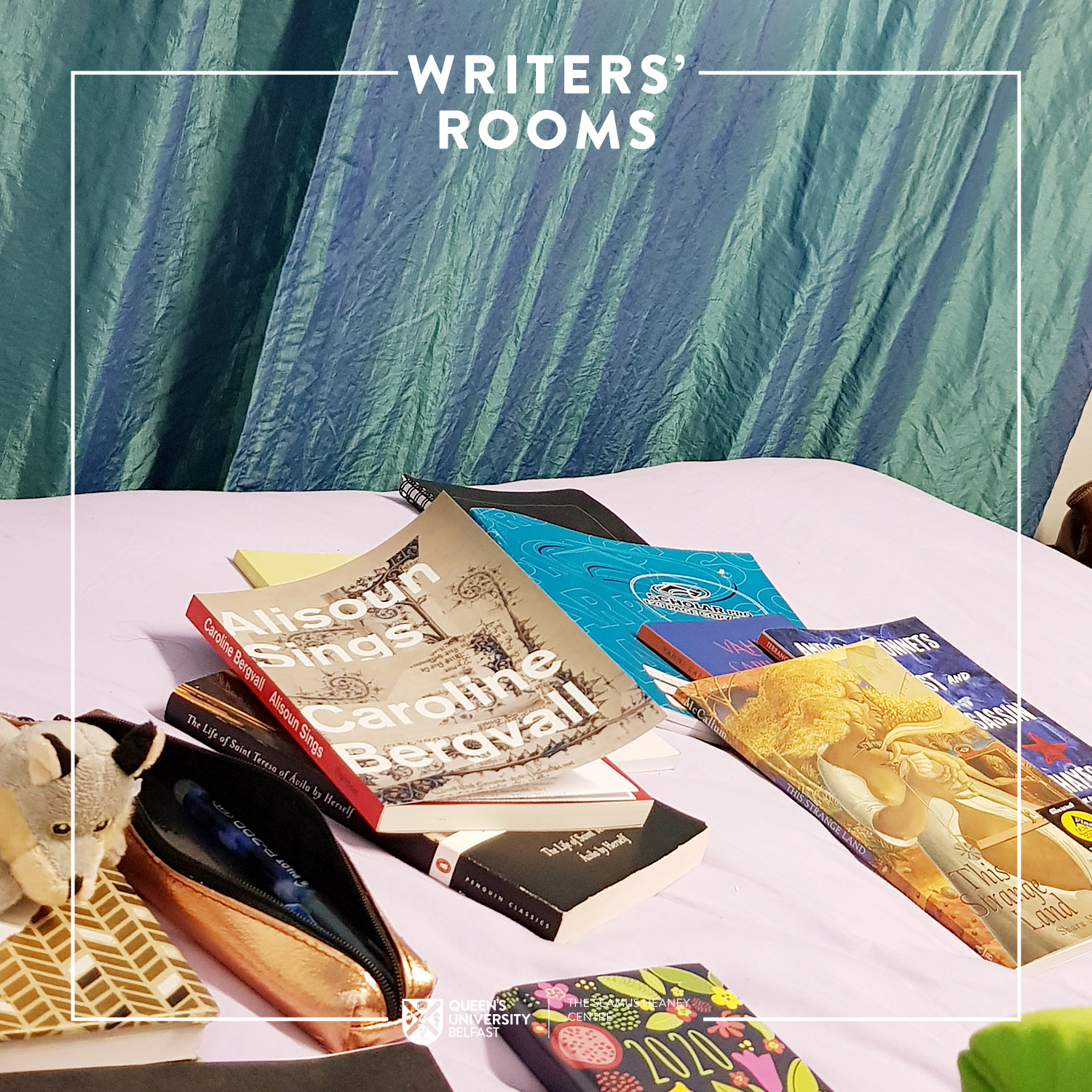

Writers' Rooms: with Vahni Capildeo

One of our SHC Fellows for 2020, Vahni Capildeo talks to us from across the Atlantic, where geckos, kiskadees, and other wild things conspire to distract from a lengthy reading list.

Where are you?

Across the Atlantic from the Seamus Heaney Centre: latitude 10.536421, longitude -61.311952, in my mother Leila’s house in Port of Spain, the capital of Trinidad and Tobago. My bedroom is the study which opens off Leila’s room, with sea-blue carpet that is two years older than I am. The window faces east onto the back garden. Kiskadees and wild parrots punctuate pre-dawn to early night. There is some creature that gallops across the metal roof and presumably launches into the mango tree. I leave it to its own devices. Disconcertingly, the North-East Trade Winds bring the roars of the lions in the zoo on a nearby hill very close. Sometimes bells are audible. I love the persistence and fading of that sound, which seems to make widening spirals, as if air were water. There’s no desk in here, in fact no chair, so I’m working from my bed. I’ve been solitary by choice for a long time, and my bed happily doubles as a reading niche. Almost as good for naps as the desks of beloved libraries.

What are you working on?

I am trying to find a livable medium between the scattering and distraction which comes from living online, and the heavy placedness which comes from being locked down. Trinidad and Tobago’s Prime Minister is a qualified volcanologist from a unit that provides training and advice on disaster preparedness, and his lockdown régime, rightly, is no joke. As for writing: there is a vague glimmering of a poetry sequence of seven days, ‘Days of Approximation’, that might and might not be a week, but I’m holding off putting anything on paper. Some people are losing a sense of time. ‘Approximation’, as a word, holds the potential for approach and proximity, and is forgiving of imperfection. However, first I must attend to emails and responses owed to friends, collaborators, colleagues, and students.

What’s that over there?

That’s Aquinas, a baby wolf from the Ulster Museum, who is not a toy. He often upsets my pencil case and hides the eraser. He is very helpful, really…

What’s that sound?

Eeek! Me being startled by a wild gecko, which chirrups juicily from between the ceiling tiles and the roof, or emerges from the air conditioner filter. The geckos have become bold.

How does isolation help or hinder you?

Hmmm. I’m not yet sure how isolation works. I’ve been thinking about quarantine, and how ‘safety’ requires redescribing everyday life. You have to be hypervigilant: wipe the doorknob; don’t wipe your eyes. The few people to whom I’ve spoken in the Forbidden Outside, and I myself, have all kinds of lapses in realization about what we ‘normally’ do – how we are, how we take ourselves for granted as being, our habits, our minutest actions – versus what now ought to be done. Redescribing everyday life is dizzying. It hurts that relation to our durational being. It requires small adjustments, the way reading in a moving vehicle does: having to keep refocusing on what’s repeatedly made unsteady. I wish that more writers were helping in this task of redescription. And what would it mean to stay true to who we continue to be, need to become? I found myself insisting to an online group that the attention which quarantine requires of us should remain just the same as the radically careful attention that every day ever deserved. Can that be true? It’s at best a partial truth. After all, isn’t being able to imagine ourselves in lengths of time, or historically, or with regard to eternity, linked to (the privilege of) being able to rest, at least a little, in our routines? To intervals of soothing self-forgetfulness?

Time for a break…?

My ‘bodymind’ takes its own breaks. Sudden sleeps have been seizing me, like the sleeps that overcome people who have medieval dream-visions. I wonder how other people are somatizing anxiety, or letting their brain rewire itself to cope? I’ve been singing a lot, beginning not with songs I like, but the ones that earworm me or the ones that are only half-remembered. They’re becoming well-known companions instead of flitting pests. Unfolded instead of jagged. I’m singing everything from the French café music my mother learnt to love in Paris in the 1960s, to Gregorian chant. It helps with breathing, and breathing helps.

What are you reading/watching/listening to these days?

Apart from unanswered email, with guilt? I’m curling up with a strange, busy silence, trying to find the middle ground between scattering and heaviness. There are past and future reverberations into this silence. For example, there are echoes from what I’d been reading before: Eduardo Kohn, How Forests Think, for one. Then, soon to be read or re-read, Caroline Bergvall, Denise Riley, and St. Teresa of Ávila are humming in chorus – my choices, for talking about writing and the body, at the University of York. Friends have sent work-in-progress: poems from Alex Houen and Dominic Leonard, for example: and this makes a delicious reverberation, promising community and future.

What might you revisit in times of crisis or uncertainty?

Were we not already in certain crisis? Many of the people who are suffering most are the people who were suffering before: those in situations of abuse, exposure, or deprivation. Lockdown exacerbates their lack of haven. The fellowship which the Heaney Centre so kindly offered me in 2019/2020 overlaps with the spring beginning of my post at the University of York, where the theme of my work, eerily, is ‘Silence, Crisis and Excess’. We had decided on this theme in winter, long before plague times descended. This was in response to the evident disequilibrium between the violent structures of our lives, and the tender needs of our environment. So the reading I’d embarked on is identical to the reading I might want to revisit. Luckily, I had brought relevant books, for what was to be a month’s visit in this year’s third job, as writer in residence at the University of the West Indies (St. Augustine campus). Still, right now I’m unreading; tuning into interiority. And, as ever, into the late Guyanese revolutionary writer Martin Carter, especially the closing stanza of ‘I Am No Soldier’:

O come astronomer of freedom

Come comrade stargazer

Look at the sky I told you I had seen

The glittering seeds that germinate in darkness

And the planet in my hand’s revolving wheel

and the planet in my breast and in my head

and in my dream and in my furious blood.

Let me rise up wherever he may fall

I am no soldier hunting in a jungle

I am this poem like a sacrifice.

Best advice for writers?

Most of my best advice is biscuit-related… I don’t know what others need. People are scrabbling for rules and judging each other: ‘don’t produce’; ‘produce’; ‘go out and help’; ‘stay home and nest’. As if rules and judgmentalism could restore even a smidgen of an illusion of control! Personally I’ve been searching out my own fears in their gross and subtle forms… If possible, keep an eye on the future you want to build and claim. If you can, organize in solidarity with others, and hope. If possible; if you can. Settle in. It is okay for there to be no clear signs. These are early days.

Our brilliant Fellow (2019-20), Forward Prize-winning poet Vahni Capildeo is in conversation with The Poetry Exchange in the latest episode of their podcast. The conversation is full of the flow of life and poetry, moving between the kind of close observation of line you’d expect from Vahni Capildeo, to wonderful musings on childhood, writing and loss.

The Poetry Exchange talks with people from many walks of life about the poem that’s been a friend to them. In this intimate yet wide-ranging conversation, Vahni shares the story of their lifelong connection with ‘Spring and Fall’ by Gerard Manley Hopkins.

“I first read it as a child, in this house that I grew up in in Trinidad. It was reading it in this environment - with the leaves falling and the birds singing - that made the poem come alive…”